This partial autobiography was drafted in the 1970s and has not previously been published.

Copyright, estate of Bertha Walker.

This electronic edition published 2016 by Alan Walker.

For more information about Bertha (Laidler) Walker and her family, visit www.solidarityforeverbook.com. Direct any enquiries to Alan Walker, mail@solidarityforeverbook.com.

Australian revolutionary activist turned labour historian, Bertha Walker née Laidler (1912—1975) was brought up in a radical household living above a left wing bookshop in the centre of Melbourne. A brief account of her later life is available elsewhere on this website, along with other writings about the Laidler family, including the full text of her major published work, Solidarity Forever! (1972), a book about the life and times of her father, Percy Laidler. See Read the book, & more.

Towards the end of her life Bertha Walker, my mother, began writing her autobiography. When she died in 1975 she had drafted only three complete chapters and the beginning of a fourth, covering her childhood and into her teens. Although the manuscript doesn't cover the author's years of left wing activism in Australia, England and New Zealand, I think it contains a lot to interest historians of radical politics — her childhood memories of Andrade's shop, the Yarra Bank, the IWW rooms and the earliest years of the Communist Party, not to mention her candid recollections of the Laidlers' home life.

More generally, the draft is packed with details of daily life — food, clothing, entertainment, transportation — in the circles in which the author spent her early life: in Bourke Street with her parents and brother; in Richmond with her German grandparents; in Corindhap with her rural grandparents; and at school in Queensberry Street.

As a touch-typist, Bertha composed directly on a typewriter. The typescript then had a few amendments made by hand. A few years after her death I gave this draft to the State Library of Victoria, together with a lot of other papers, which are now part of the Library's manuscript collections. The Library staff kindly made me a photocopy of the draft autobiography, and this copy is the source of this digital edition.

The text is written in a very free-flowing, informal style, in contrast to most of the writing in her book about her father's life and times, Solidarity Forever! As such, it conveys something of the author's personality, as is appropriate in a set of memoirs. Perhaps if she had lived to prepare a final version for publication, she would have rewritten some passages in a more formal style, and perhaps she would have removed some of her blunt comments about family members and others. I have reproduced here the draft manuscript, as is. Beyond correcting a few obvious typographical errors, the wording and punctuation have not been changed.

Certainly she would have done whatever she could, before publication, to verify the factual accuracy of her memories. She recalls details from quite early in her life, but doesn't claim to remember everything. She notes that she has no direct memory of her teddy bear being cut open during a police raid. I feel that her recollections are generally accurate. But, given especially that the manuscript was only a draft, she may have misremembered some details. She tells of reading the news reports of the Hungarian revolution to her grandfather, during the illness preceding his death in 1924, but the Hungarian revolution was in 1919 — perhaps she was reading to him about some other revolutionary upsurge in Europe.

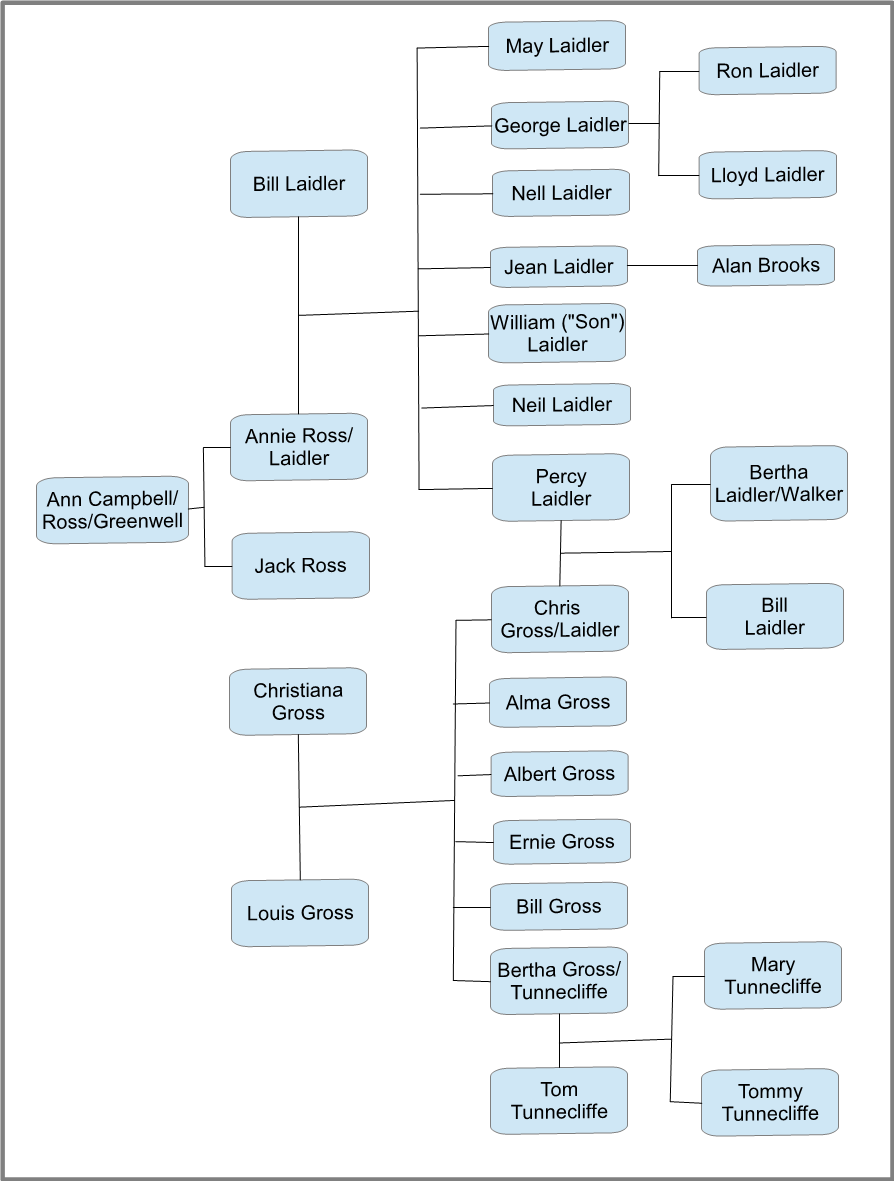

I decided against providing explanatory footnotes covering historical events mentioned in the text, but I have created a family tree diagram showing most of the members of the Laidler and Gross families mentioned.

The unconventional set of values Bertha Laidler absorbed from her upbringing are revealed in passing comments. The shop assistants at Andrade's who were "nice revolutionaries". The reprobate remittance man who turned up years later, "a reformed character, married with children and a member of the Communist Party".

Some of the comments in the text may cause the progressive reader of today to raise an eyebrow: the remarks about "women libbers", about rural idiocy or about her doubts of the safety of vaccinations (although such doubts were probably more warranted in the times she was writing about). Any reader well versed in the history of the international communist movement may be struck by the author's enthusiasm for the 1929 intervention by the Comintern in the affairs of the Australian party, to clear the way for the sectarian "social fascist" policies of the early 1930s. Yet she also writes with sympathy about the rebellion of a loyal party worker against the "vindictive" attacks of the new leadership on the old.

On a few occasions sentences were left incomplete in the draft, with further details to be filled in later. These instances are noted in the text. The chapter titles for Chapters 1 and 2 were provided in the manuscript, as were the two section headings in Chapter 2. I gave titles to Chapters 3 and 4 and a title for the work as a whole, My Revolutionary Childhood, in recognition of the period of the author's life mainly covered.

Alan Laidler Walker

August 2016

Family tree, showing members of the Laidler and Gross families mentioned in the text.

CHAPTER 1

I was born into an unusual household in that both my mother and my father were revolutionaries. They were both active in the movement. I always called them by their first names, Chris and Perc.

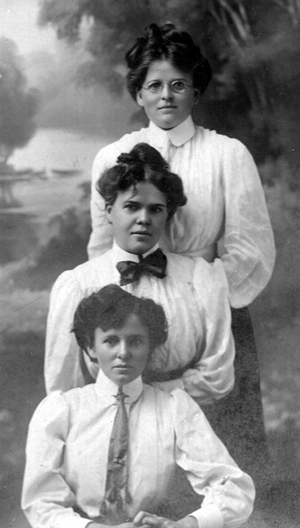

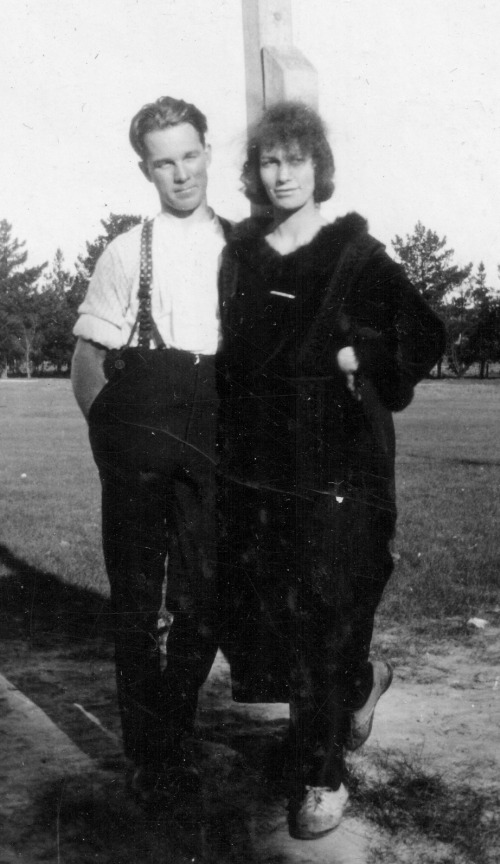

The Laidlers - Chris, Perc and Bertha

Chris was a feminist as well as a socialist. Her father was a socialist in Germany and left because of its Prussianism. Chris was active in the Clothing Trade Union as a tailoress and I think she attended conferences and was on the executive. Earlier she had been in service working for the toffs in Toorak. She was a courageous and passionate speaker from the soapbox on behalf of the Victorian Socialist Party and she became an ardent follower of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Her activities ceased when I was born because she put her child before her personal interest. After two and a half years my brother was born so she had a double yoke.

We lived in Port Melbourne, which I don't remember then we moved into 201 Bourke Street and lived in two rooms on the 2nd floor above Andrade's Bookshop, which Perc managed. He sent revolutionary literature all over the Commonwealth and as well published a lot of pamphlets and the first Marxian periodical The Proletarian. The shop was a centre where revolutionaries met so Chris was not completely cut off from news of the movement. She could come down in the shop and meet the rebels and many came up to her kitchen to talk to her. As well as the politicals she had a lot of women visitors, some of them old German friends. Although born here she could speak German, which according to her was a "very low German".

Chris had a very sympathetic nature and women and men came to her to unburden themselves. Her sister, Bertha, says she was so sympathetic that women used to tell her their troubles when she was only six or seven years old. The family ran a laundry and Chris would take it in baskets up the Church Street Hill at Richmond, to the homes of the many doctors who lived on the hill. Women would stop her even then to tell a tale of hardship. At Bourke Street it went on all the time. One poor old German lady had been told by a fortune-teller that a man would come into her life. Every week she brought a sack of produce from the farm to the market and would call on Chris and say, "Do you think he will come?" She spent her life in the phantasy that some lover would appear to rescue her from her life of drudgery and her husband. Another was a wealthy woman who was unmarried and Chris would try to make a match for her but as Chris only knew poor men she failed in this. Rich ladies find poor men rather unattractive.

Chris made our clothes herself and fed us well. The emphasis is on good food in German households. Our vegetables were smothered in butter and no doubt that is the reason they were more attractive to me than most children. We had porridge pretty well every morning and it was a great emancipation when she read in the paper that cereals were to come on the market in great variety. As early as 1900 or before there was a cereal called "force". It was emancipation for me too as I hated porridge, morning after morning, and I think most children did, too. After all, it is the gaol diet. On Sunday mornings we had sausages. The only alternative to porridge in those days was bread and milk. The bread would be cut in small squares, sugar sprinkled on it and topped off with warmed milk. This was regarded as a satisfactory food for children. Chris cooked some German dishes, three we liked were raw meat, red cabbage and a sweet, rot gutza. The raw meat is prepared by mincing rump steak, grating raw onion, adding pepper and salt and a raw egg. It is delicious on sandwiches and Chris usually made them for parties. After the guests had eaten them and they usually wanted to know what the delicious filling was, she would tell them raw meat. I'm afraid she once gave them to some vegetarians (as she thought all these health ideas quackery). They though them delicious but I don't know whether she told them what it was. We used to eat it up off the plate with knife and fork and usually had it with potato salad. Someone remarked to me a couple of years ago that she made the best potato salad he ever tasted. She used a raw egg dressing. The red cabbage is done with caraway seeds, a knob of butter, a little sugar and when finished doused with lemon juice. Rot Gotza is delicious but I have only made it once myself because it is too much trouble by my standards. You cook blackberries, raspberries and red currants, then mash them through a sieve. Some arrowroot is cooked into it and you have the delicious flavours of the fruit. It is now imported in packets but tastes like a load of chemicals.

Vaccination was usual but there was an Anti-vaccination organisation. My parents refused to allow me to be vaccinated as they were against it. Perc was fined one pound but I was not vaccinated. Probably it was just as well because when I was vaccinated on joining the WAAF I was so ill I was put in hospital for a couple of days. If that was my reaction then it might have been fatal as a baby.

Perc was completely dedicated to the movement and we did not see so much of him as an ordinary father. He was always at meetings, after the early closing in shops came in. In the beginning the shop was open every night. Both Chris and Perc used to take myself and my brother Bill out together at times. Chris felt we were deprived by living in Bourke Street and used to take us to the gardens — Fitzroy, Treasury and Botanical in reasonable weather. In hot weather we got on the dummy of the cable tram, preferably the front and went down to Port Melbourne or South Melbourne. Sometimes we swam in the water. At each terminus was a merry-go-round and this was a great delight. Sometimes we came down on the tram to Port and walked to the South terminus and came back on that tram. In cold weather we took the tram to the Johnston Street Bridge and walked to Studley Park.

One of my earliest memories in Bourke Street is falling down the stairs. They turned around halfway down so you started at the top, or somewhere near it, turned around and went screaming to the bottom. The shop assistants, who were mostly members of the IWW would rush in to see if I was hurt. I must have rolled down dozens of times without much injury. There was a gate across the top but either it was left open or perhaps I was able to open it.

Most of my earliest memories are political. This had an influence on me. The Yarra bank and the IWW rooms in Little Bourke street are my main memories. The IWW was made effectively illegal in July 1917. I was five years old on the 8th of July, 1917 so my memories of the IWW were probably when I was four. I remember we used to go to the meetings every Sunday night. I was taken by the hand and had to climb what seemed narrow, dark and steep (two flights) of stairs. I don't recollect being bored. There was always plenty of singing of the tricky IWW songs. Sometimes a social and dance was held. Once Chris's handbag was stolen and she couldn't get over how a comrade would do such a thing. But that was the way of many of the IWW people.

Bertha Laidler

My first memory of the Yarra Bank was when I must have been a toddler, because Perc held me by the hand all the time. The reason I remember a particular occasion is that I was laughed at and must have felt some humiliation. Perc was talking to a group of 3 other people, one of whom was Flo Delalande, an IWW girl and two men whom I forget. While they talked I kept tugging at Perc's hand and said, "Go on Perc, get up and speak!" I must have been accustomed to seeing him on the platform because it seemed abnormal he was not on it. Finally the others stopped talking and one said, "And what will he speak about?", to which I replied, "Poverty." Words I often heard spoken that stuck in my memory were poverty — orthodox — unorthodox — radical — economics — Marxism — Karl Marx — Liebknecht — Luxembourg.

The bookshop was open at nights, when I was very young. All the IWW chaps used to come in and meet each other at the shop. Most of them made a fuss of me. They nursed me and picked me up and put me on a narrow ledge where books were displayed, so that I would be level with them. My nickname was Bubbles. The amount of attention I got then was greater than at any other time in my life and I think it was effective in giving a certain amount of assurance, which probably helped me through life.

I am not mentioning this in the field of memory but we were raided by the police while the IWW was still legal and my Teddy bear was ripped up by the raiding party to see if anything seditious or explosive was concealed in it. This was told me later in age.

As well as being a political bookshop, it was also a theatrical shop selling conjuring tricks, masks, grease paints and plays. There was a ventriloquial dummy called Sammy, which Perc would take out to parties of our cousins and do an act. I was very frightened of the dummy, thinking it was alive. When the shop was shut and I had to pass it to go to the lavatory, I would run for my life.

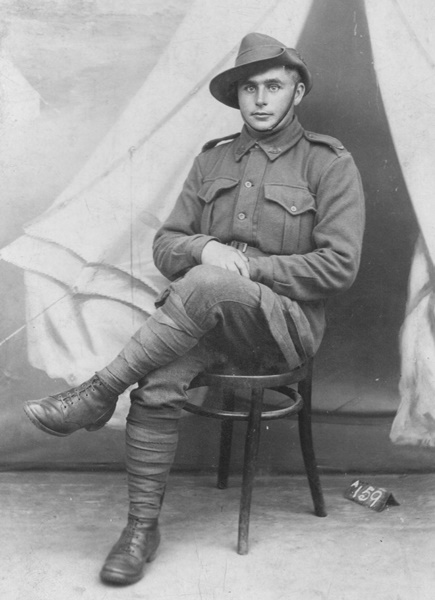

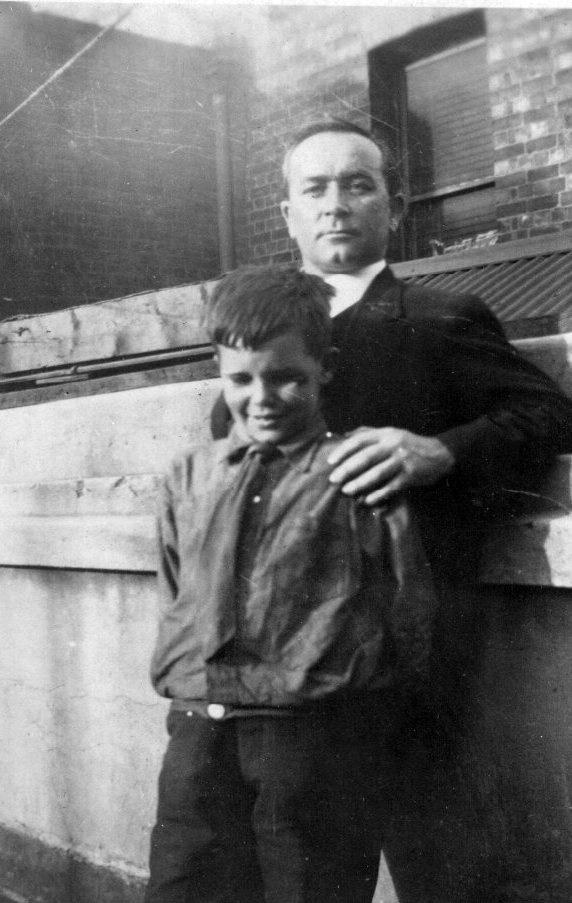

Neil Laidler

The war impressed itself on me when the Corindhap (the town my father came from) soldiers came into the shop en route to the war. His two brothers William (Son) and Neil, a cousin and others from the township were all there. I remember them winding their puttees around their legs and Perc talking seriously to his Brother Neil. In later years I learned that Neil had not wanted to go to the war, but did not like to shame his parents. Neil went. He wrote back to Chris, "For god's sake stop anyone you can from coming here." Neil was killed and Perc never forgave himself because he felt he could probably have stopped him from going.

Even before Bourke Street I have memories of Richmond. I remember being wheeled around in a wicker pram. One time I was left in the pram outside the Richmond Post office for what seemed like hours. I remember being taken round to see my mother and brother Billy when he was born. I would have been 2½ years old then.

We were both born with the help of mid-wives, as was the custom. Probably the rich had doctors. I was born with a caul which is a skin that sometimes encases the head and part of the body of a newly born child. The midwife said it was lucky and to preserve it and put it on the nearest newspaper. She was horrified to find it was on the paper Freedom the journal of Anarchist Communism, published in England. The superstition is that if you have a caul with you on a ship it never sinks. Trouble is I never had it with me whenever I sailed. If I could find the right superstitious people I could have made a living safeguarding their ships for them.

How did I spend my time at Bourke Street? We had a roof yard surrounded by a cement wall. It was 2 flights up and must have helped demolish the nerves of Chris for fear I would go over the wall. We overlooked Bourke street, a magical street. It was the hub of everything for life flowed through it. I could look out the window and be entertained for hours. The cable trams, the horse cabs, tradesmen's carts, and an occasional hansom cab went up and down the street. At the hour of evening I never missed the lamplighter who would come around and minister to each separate gas-lit lamp-post by unlocking it, running down the globe and applying a large 8-foot long lighter to the wick. This was fascinating. In the morning, and all day, the block boys were up and down. These boys had little carts similar to MCC carts today. The job was to scoop up horse dung and put it in the carts and then empty them into little insert metal bins under the pavement. They had a strike once. One boy stayed working and tried to do the work of the team much to their amusement and the amusement of the whole Bourke Street crowd.

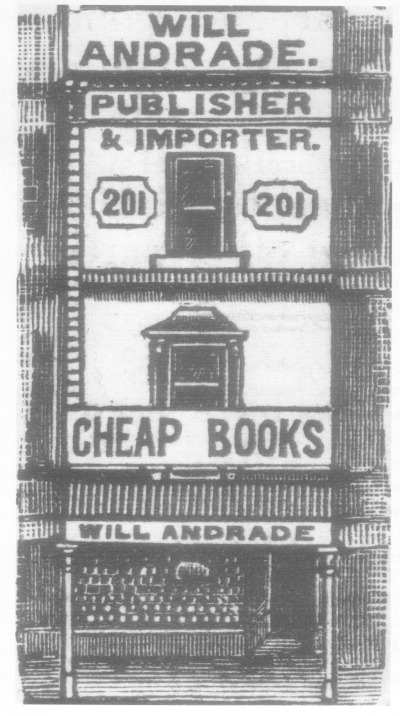

Andrade's shop, some years before the Laidlers were in residence. (Tocsin, 1901.)

At night from our window you could see two theatres, one the Star had a great lit-up star on the top and lights all around the sides of the building, running up and down. Every day there were fights outside the Parers hotel, opposite. There was always something to see in Bourke Street. Next door was the Queensland hotel (now Carlton) and there were often brawls out in the back lane. The end of the roof yard overlooked the lane which ran down the side of the King's Theatre. We could see all the girls dressing and running down the stairs to stage when the call-boy would give his final call, preceded by "First Call", and "Second Call" loudly shouted out so all could hear. Then they would race up again and change. It was a long way to the stage for the chorus girls. The big actors were closer. We saw quite a bit of life in the theatre, especially when the pantomime was on during the Xmas holidays. I remember once Perc swung a bottle of beer across the lane on a rope to a chorus girl who deftly caught it on a very hot summer day. We got to know the dresser and other regulars in the theatre. I was invited to join the pantomime once when they were short of children but Chris did not approve. She didn't think girls should be appearing with dresses up to their groins for the benefit of the salacious.

Barry Lupino of the famous Lupino acting family was at the Kings. He had been a founder of actors unionism and was a socialist. Somehow he became known to Perc and Guido Baracchi. They used to be always in his dressing room having discussions, or Perc would yell across and down the lane to him.

It took a long time to get dressed in those days. We had button-up boots which were buttoned with a button-hook. We wore gloves, which had to be such a firm fit that it took about 10 minutes to roll them on. Children wore stays which had buttons at the bottom to which you hooked the button hole which was on your pants. Children usually wore a flannel singlet and two petticoats. Bras had not been invented or if they had then were not in wide use. Ladies wore slip bodices. They were bodices for the top and a woman would wear several of them at once. The old ones nearest the skin and the lacey one on top in case it showed through a blouse. In winter a spencer or flannel bodice would be worn underneath the frilly one. Women usually wore two petticoats, one warm and one decorative. Corsets were long and difficult to adjust. In all, getting dressed was a big operation. The fashion was high necks and long skirts. Someone related to me how her mother related to her that when she was a girl, the girls would get together in a room, pull down the blind and open their blouses at the neck, giggle and think what daredevils they were.

Though we lived in Bourke Street we frequently visited our grandparents in Richmond and my mother's sister, Bertha who married Tom Tunnecliffe, the ALP politician, at their home in Gardiner.

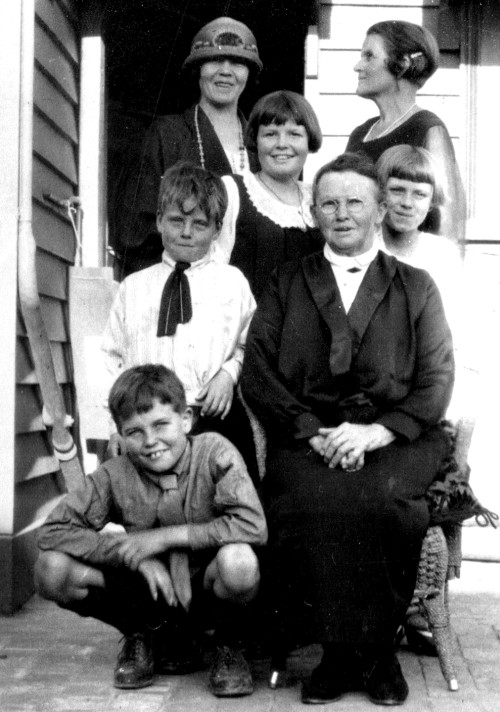

Family group: from top left, Chris Laidler, Bertha Tunnecliffe, Bertha Laidler, Tommy Tunnecliffe, Christiana Gross, Mary Tunnecliffe, Billy Laidler

My grandparents were German and lived a very organised life. My grandfather had a garden and produced a great number of vegetables. He kept a tub of humus and would go out on the street and scoop up the horse dung. There were plenty of horses around and not many cars. In later years I went back and looked at it and was amazed how small the garden was. We always had in season rhubarb (dessert every night), silver beet, radishes, tomatoes, lettuce and some root vegetables. Grandfather was always a radical and would get into great tempers over the betrayal of the workers. He got two papers every week, the Labour Call and the Worker. The Labour Call annoyed him but the Worker under the editorship of Henry Boote was not too bad. Grandpa used to go around selling the Worker until someone asked him what he got out of it. He stopped canvassing it, at that imputation.

Food here was plenty but plain. Again everything was smothered with butter. Jam, cakes and biscuits were all home-made. They used to give me every morning a glass of warm milk with a raw egg beaten into it, just to build me up when I didn't need it. It was grandma's custom when I went to bed to take off the flannel singlet I wore during the day and put on a different one for sleeping. The day one was "aired".

Sometimes some old German friends of my grandpa's would come in and play cards, my grandpa wearing a decorated smoking cap. [Handwritten note inserted in typescript by author: "Cigars smoked" -Ed.] When my grandma had a birthday there would be a visit from about a dozen old German ladies, and some of their children. Each would bring a bunch of flowers as well as any other gift.

My grandmother must have been irreligious, as well as my grandfather. Nearby was a very religious family. All the children went to the Christian Endeavour organisation. One of the girls became pregnant. My grandma said, rather maliciously, "That's what happens when they go to Christian Endeavourance."

My grandmother would come into the city every Friday and take me off my mother's hands to give her a break, or perhaps for company for herself. She would take me to the matinee at the Gaiety Theatre, a few doors down from the shop. It was in the Victoria Arcade and here one could see Melbourne's lowest class vaudeville. It was best known for its association with Stiffy and Mo (Roy Rene). It was on these boards that the four letter word was first used by Stiffy. He didn't actually say it, he contrived to spell it and was banished from the theatre. My grandmother used to laugh herself sick at the unsubtle pornography here. It went over my head.

Meanwhile my grandfather on his visits to town would go over to a German delicatessen in Russell Street, made by a man named [Uncompleted sentence in manuscript. -Ed.] He would come home with good rye bread, black bread, liverwurst, mettwurst and braunsweiger. Everybody ate white bread and it was not easy to get these kind of delicacies excepting by coming to town to get them. Grandfather had a special board he would cut his sandwiches on, using a special knife. One of the favourites was liverwurst with a slice of raw apple.

When the family first came from Germany they lived in Adelaide for a couple of years. Arriving in Melbourne they lived in Richmond. First they had a two roomed house in Russell Street, then moved to Church Street near the bridge. Here hot water from the brewery would flush the drains and the kids would play in it.

Next a house was bought in Amsterdam street. Grandpa was a bricklayer and eventually build two houses from which he got rents and he himself bought a wooden house next door the brick ones in Mary Street. Grandpa went to Africa three times. The oldest boy Heine (Ernie) also went and Bill Gross went at 18 years and made it his home country. German tradesmen in poverty here would get the fare to South Africa and make some money. Grandpa came back with 300 golden guineas from his first trip. He used to do all the cooking for his companion from Australia, Uncle Burmeister. Grandpa was there during the Boer war and became a special policeman on the side of the Boers against the British. I have never been told why. He was against all wars and police but possibly everyone was conscripted and he insisted on non combatant duty.

The Gross family house in Mary Street Richmond today. The two-storey structure at the rear is presumably a later addition. (Photo Alan Walker 2011)

At home grandfather taught all the children the songs of Gilbert and Sullivan and various operas. Tannhäuser and the Wagner compositions were all learned around the table. He had been in a choir at home in Hamburg and it was probably here he met Grandma as she was a choir member, too. She was a soprano and he was a tenor. He was also in a choir in Melbourne in the Verein Vorwärts the German socialist organisation. This was how they filled in their nights at home. Singing, playing cards and dancing. Alma went into some place in Collins Street and learned the Lancers and all those dances known as the sets. She came home and taught the rest of the family in the kitchen. How they fitted in even after taking chairs, table and sofa out, is hard to know. Bertha says they had to cut their cloth to fit. Ernie would provide the music on a mouth organ. They were a fairly happy family despite poverty. Outdoors, picnics were the thing. Sometimes a picnic would just be held in the gardens but other times a horse-drawn vehicle took them further afield.

The Tunnecliffes were our rich relations. They had what seemed a big house. It had a grassy yard out the back, trees, flowers and Gardiner itself was countrified. If you left the house and went beyond it was like walking in the bush.

The Gross sisters, Bertha, Chris and Alma

Bertha was born in 1881 in Germany. When she was 28 she went off on her own to Western Australia. She arrived at her sister Alma's in Kalgoorlie. Alma had married a miner who searched for gold all his life. The only time he got near any quantity he had given up and someone else came along and dug out a fortune. This really got him down and he couldn't leave a useless shaft after that in case there was gold just below. Alma had a pretty lousy life.

Bertha went to the races on her first day in Kalgoorlie and lost all she had, £5. She had to write home for £10 and then went up to Mount Sir Samuel and got a job in the local pub. She was a parlourmaid-housemaid and general factotum but when asked to serve in the bar refused on principle. She was anti-alcohol. Also it was the days when a barmaid was regarded as a lady of easy virtue. She was treated wonderfully well by everyone and was tipped off by her friend the yard man to get out before the wet season. This she did. She returned to Melbourne after about two years away. While at Mount Sir Samuel she saved £50, a princely sum. It was a pretty adventurous thing for a woman to do then. Her attitude to drink was such that she would not dance with a man who had beer on his breath nor would she dance with an onion-breath man. One man at the German club was nicknamed "beer & onions" by the girls. Bertha brought home from WA a horned lizard which she thinks was called a mountain devil. It died of the cold. She remembers wearing a hobble skirt and it was the devil to get on a tram. Men whistled at her and everyone in a hobble skirt because you could see the ankle as they got on a tram. She wore a feather boa, these were fashionable slung around the neck.

Bertha was a good politician's wife. She used to refill 14 vases with flowers every day at Gardiner. What intrigued me was her butter pats. She would expertly make butter rolls with their pattern of lines to put on the table. We always had Xmas dinner at their place. Perc would do some tricks for the children or bring Sammy along. After tea the sisters would get around the piano and sing "Two Little Girls in Blue", "Because", "Excelsior", "Jerusalem" and other favourites. They used to sing at other people's places, too, and Bertha at the socialist party meetings. Tom and Perc would get in a corner and hammer at politics. Perc would jibe at Tom as a politician but they had an amiable relationship. Tom was already cynical.

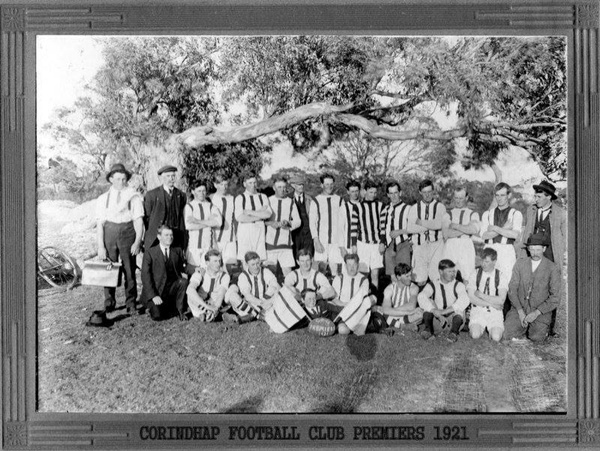

Patriotic procession in Corindhap during First World War

The other place we went was Corindhap. This was a long trip. Train part of the way then a coach with horses, changed at the halfway house and a new team to end the journey. The Laidlers had the post office. There was a stable for horses which were the main attraction to me, especially a little pony called Billy. My mother hated going there because she knew they hated her for being a German (although she was born in Australia). They despised even the English as foreigners. When my brother contracted polio she blamed it on to a trip to Corindhap. My grandfather was a great tease and used to think I was a cissy. He delighted in making me swear. He had a trick of telling you to say, "I chased a bug around a tree" — speeded up you were saying "bugger" before you knew where you were. I thought he was wonderful.

Bertha's brother Billy, with Perc, 1925.

When Billy got polio it affected one of his legs. Perc was devoted to helping him for many months or possibly years. Every night he would massage the leg. Bill had to wear an iron on his boot. He, like Chris, had a hot temper. Possibly the illness and condition of his leg had some effect on him. At any rate he hated me and as I was older and stronger I could win in the stand-up fights we had. He developed a great habit of aiming forks and knives at me. I would race for the door and just get through as the knife struck. Probably his temper make him aim off course. It was pretty frightening. Perc gave him anything he wanted and gave in to him continually. Because of his polio he treated him as something out of the ordinary and this tended to make him selfish in the early years.

Chris quite often went to balls and other affairs, invited by Bertha. She would always bring us home a piece of cake wrapped in a paper serviette, which she had put in her handbag and would say next day, "You couldn't go so I brought this for you so you could share in it."

I remember she once went to a fancy dress ball as a salvation army lassie. She sprinkled her costume and hat with phony banknotes to indicate her contempt for the money making salvation army, which had nearly as much capital in real estate as had the catholic church. People give and think it is for the poor while their capital accumulates and accumulates.

When Val Noone, editor of Retrieval interviewed me he asked what it felt like to be brought up in a revolutionary atmosphere. I replied, "It seemed normal." Before I started school I already had some education in politics, things theatrical, politicians, Germans and low class vaudeville.

CHAPTER 2

It was time for me to start school. Extraordinarily Chris started to talk of me going to the Catholic Girls' school in Parliament Place. This was the nearest school to us and perhaps her motive was expediency. She began to talk about how the nuns taught music and sewing etc. Why she should think I would be interested in these things is hard to know. She was probably thinking of the distance she would have to cover to take me and pick me up. I don't know what Perc said about it but I can't imagine he would have wanted me in a religious aura.

Reason prevailed and I went to Queensberry Street State School, Carlton. It was a long way to go but there was nothing closer. I had been briefly in a kindergarten which was in Carlton but nearer the city. I think Perc used to take me quite often and Chris would call for me. This was a school of poor children. Very few were well fed and some were most likely starving. We had a wonderful teacher in the babies grade. Every afternoon without fail, she would say, "My mother gave me too much lunch today. I'm going to give a sandwich to the best behaved children." She would bring out a huge stack of sandwiches and distribute them with some hot cocoa or milk in a thermos. I behaved perfectly but she never gave me a sandwich. It upset me and I told Chris of my sorrow. She said, "She is giving it to those that haven't got enough to eat and she knows you get all you want, that's why you don't get any — but don't tell any of the other children." This went on right through my school life — my parents kept nothing from me but were often telling me "Don't tell the other children." This applied to god, Father Christmas, babies and various political events.

Chris with her usual sympathy got talking with the other mothers waiting outside for the kids and as they were so poverty-stricken she was always bringing along old clothes (already hand-me-downs to us), home-made jam and other food.

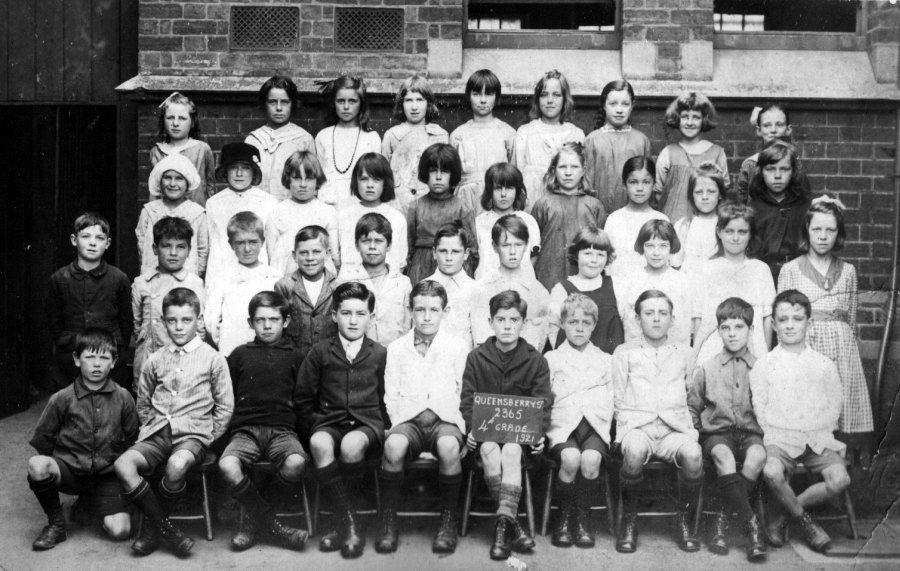

State School 2365, Queensberry Street, North Melbourne. The school closed in the 1930s but the building still stands. (Photo by Laurie Burchell, from State Library of Victoria, Laurie Burchell Collection, H2006 165/109. In copyright but use is allowed provided the creator and SLV acknowledged.)

I moved up to grade 1 and got my first school bag. I was so proud of it I kept it on my back all day. The teacher didn't say anything but somehow I must have mentioned it at home and Chris thought it a great joke. I behaved in a more sophisticated and less property-conscious manner next day. I went on to what was called the country room. This had three rows of desks, covering grades 1, 2 and 3. I stayed in the country room. All through my school life, from the babies up to the 8th grade my best friend was a Chinese girl, Dorothy, known as Dot. We were a student training school and our kids broke the heart of more than one. One chap had a talk with my mother and said he was giving up teaching he realised he couldn't handle the children. Our crowd were pretty rough and tough. We had the police walk through looking for stolen goods. A big boy beat up a teacher. I got on alright except for having one fight after school with a girl much bigger than I was. She gave me a sound drubbing. I made my big political gesture by deciding to refrain from attending religious instruction, which was on the agenda one morning a week, when a visiting churchman took the class. I had to bring a note to say that I was not to attend religious instruction. When I found that this meant I had to spend the time doing schoolwork while everyone else was enjoying themselves at religious instruction, I had the note vetoed. The religious instruction teachers had no control over the children so it was just a period of yelling, screaming, throwing pens up to the roof, aiming spitballs and dancing round. The ordinary teachers did nothing at all to help maintain discipline but appeared to regard it as time off for themselves.

Chris had soon got tired of calling for me and made an arrangement with a teacher who came through town to take me on the tram with her and drop me off at Bourke Street. One night, either by accident or design, she went without me. I was in a bit of a panic as I had no confidence to get home on my own. Had I been taught to do it from the beginning it might have been better but once coddled you are reluctant to use initiative. I was in the first grade at this time so would be about seven. There was a care-taker in a house in the school-yard and I knocked her up and told her my plight. The good hearted woman put her coat on and took me home. I think I must have been taught to go to and fro on my own because I didn't go back to the teacher as escort.

After learning to get myself to school it wasn't long before I was given the task of getting someone else there. In the 1920s the first Communist Party in Victoria was formed with headquarters in Swanston Street, just around the corner from Bourke Street. We used to go to lectures here, too as Perc was a member. Carl Baker was the Secretary and he had a little boy. I used to call in each morning to pick him up and then bring him back in the afternoon. Mrs. Baker had a little baby as well. Chris took pity on her poor condition, as Baker received little pay, and collected some money for her, thinking it would be spent on clothes or food. To her disgust, Mrs. Baker bought a gold brooch for the baby with the money. Chris must have felt like swiping her across the face for her stupidity. The people who gave money were all in poor circumstances themselves and it was a pure waste of money from Chris's point of view. When my brother started school I took him there until he was old enough to look after himself. When my cousin, Mary Tunnecliffe was little, before she had started school, she stayed at Bourke Street while her mother and father were in Sydney. It was a great ordeal for her. She had to sleep in a bed with me when she was used to having not only a bed, but a room of her own. The clanging bells on the trams stopped her sleeping. She had brought some beautiful handkerchiefs. Chris decided I should take her to school with me, but she wouldn't let her take a costly handkerchief for fear it would be lost or stolen, instead she pinned a piece of rag on her dress. Mary still remembers the shame of it all. We didn't worry about the Bourke Street noise but when we went to the country, the quiet was oppressive and it was hard to sleep because of it.

Most of the kids at school had no shoes or boots. I had them but preferred not to wear them. My mother would start me off with them and as soon as I was on my way I would take them off and carried on walking through spittle-spattered Bourke and Swanston Streets oblivious to the filth. I was given great lunches to take to school. Sometimes a jar of jelly and cream. I always had fruit. Sometimes hard boiled eggs. Some kids from a large family who appeared to have no lunch would come up and ask me for banana and orange peels to eat. Now, I can't imagine how Chris could be so insensitive as to have me gorging myself in front of so many hungry children. I am ashamed I was so heedless myself. Occasionally I went with a girlfriend to her home near the school where she had the task of setting the table. Apparently her mother worked and she set it ready for her. This girl every day had one slice of bread with jam on it, no butter. It was a great delight on Mondays when I was allowed to buy my lunch (because the bread was stale). I was given sixpence. There were four choices for a bought lunch. You could buy a pie or pastie for 3d. and three penny cakes. I usually got a napoleon, vanilla slice and bird's nest. You could get 6d. fish and chips. 3d. for the fish. Another lunch we liked to buy was a little cottage loaf from a nearby bakehouse and a 3d. pickled cucumber. Chris would be annoyed when I told her I had such an un-nourishing lunch. Or we could have raw saveloys and a loaf of bread.

Once at school we had to get our parents to fill in a sticky-beak questionnaire that would do credit to American big businesses. One question was the nationality of grandparents. Chris didn't want us to suffer any odium from our German background when anti-German feeling was pretty high in the early post-war years. She put down our German grandparents as Americans. I suppose she had enough sense not to have told grandfather or he would have been furious. So, somewhere in the records I am down as part American which is now a greater ignominy then being part German.

It was when I was in the third grade that Chris had a breakdown. Life in 2 rooms with her own standards of discipline for work and with Perc's interests mainly outside the family compelled her to go away for six months to Albany in W.A. to stay with Alma. My brother and I were farmed out to relatives. I went to stay with Chris's brother Albert and his wife May and baby girl, Gwen, and Bill went to grandmother and grandfather. Albert and May lived in Burnley and I attended the Burnley school. This wasn't a bad school but then we all shifted in with my grandmother and grandfather, who had divided the house into two sections. I then had to go to the Brighton Street school, Richmond. I dreaded this place as they used to cane you with a long cane. It was a most unsympathetic school. This school was the one attended by the Gross family as children, and Chris had been a pupil there. It was a strange fact that among the Gross's the ones born in Australia probably rolled their r's more than those born in Germany. When Chris went to school the teachers used to put her up on a desk or table to recite a verse that was full of r's just so they could laugh at her rolling rendition. The verse went something like this:

The crossing sweeper.

They could not cross the street beneath the widespread sky.

To each other they were bound by poverty's strong tie.

There was a lot more and it proved a regular diversion for the bored teachers. Chris had been nicknamed "candles" because her nose was always running — the family ailment of catarrh.

It was like going home to get back to Queensberry Street, Carlton. Richmond was full of street cries, almost like London. "Rabbit-o" was one of the most frequent and you could rush out and buy freshly caught rabbits. Then there was "bottle-o" to pick up bottles. There were others but I forget what they were. It was a more normal life in that I had Cousins Chris, Freda, Louis, Ella and Francis living not far away and could go and play with them. I used to do some of the messages and one of the nicest used to be going to the dairy. We always got the milk twice a day. We had no ice-chest, only well-off people had that sort of luxury, so we would go down in the morning with a billy to get some and then again about 5 o'clock when the Gippsland train would be in with the early morning's milk. Grandfather had built a small cellar in the ground between the two houses in a narrow strip of ground. It was so narrow the sun did not get on it and here soft drink was kept, butter, milk and other of the most perishable things.

I would be sent for threepennorth of soup vegetables and for this you got a carrot, a parsnip, a white turnip, an onion, a piece of celery and parsley. At the grocers you always got free, a rolled up twist of boiled lollies.

At my grandparents' place we always had Hansards hanging in the lavatory. No doubt copies were sent out by Tunnecliffe. My grandfather would read them and fume, then they were put in the lav for us to read and then wipe ourselves on them.

Chris came back and was happy to see us and much better tempered. She had sat on the pier at Albany catching fish, which were so plentiful you could see them in the clean transparent water swimming round and taking the bait. While she was away Perc would come out and see me every Saturday and I suppose he used to see my brother once a week, too.

It was nice to be back home with Chris and Perc.

Queensberry Street School photo, 1921. Bertha Laidler in 2nd row from front, in dark pinafore.

I did half a year in the fourth grade and half a year in the fifth grade and then on to the sixth. We had a cooking school at Queensberry Street and it was really run as a business. We were not taught to cook. Once we could do one thing we did it every week. The dining room would be open at lunchtime to local businessmen who got a three course lunch for one shilling. We did the work and I suppose the Education Department paid for the food. I nearly always did Cornish pasties and cabbage. The meat in the pasties came from scraping every shred of meat off the soup bones. I thought this shocking but there would be less, if any, meat in shop pasties today. After the diners left we had ours for which we paid sixpence. It must have been hard for some to produce it. Usually there would be nothing much left. All the best dishes were gone. The diners would have boiled pudding and this would be gone. Some child would be told to whip up some blanc mange for us.

We had to go all the way to Boundary Road, North Melbourne for sewing class. I could never sew and got my mother to do it all, while going through the motions in class. Usually she had to unpick it or start again. The only thing I did myself was some knitting, turning a heel. At the end of the year I was complimented on the knitting. I suppose it was a subtle way of saying they knew it was the only thing I did.

We had a long walk to Royal Park for sports, but when we returned home the teachers had left us and we would whip behind on the big timber wagons and brewery carts which went up Flemington Road. I was no good at sport, too fat and disinterested. The only time they put me in a rounders team I was useless.

We put on a play at Wilson Hall in Melbourne University. Possibly other schools were involved. I had a part in the play. It was a play with a moral. I represented the healthy girl but the trouble was I had only about one line to say. I fought against this and tried to get a better role, not because I cared about my schoolmates seeing me in an inferior role (I was lucky to be in it at all), but I knew my mother would be there and bound to mention it. She did! I suppose she was disappointed although I had warned her.

I had my experience of thieving while at school. For a time I used to go around to a sweet shop, lean across the counter and take some lollies out of the showcase. The shopkeeper would be outside. I felt a bit deprived because poor as the children were, they seemed to have a lot of money for lollies. On health grounds I didn't get many lollies. A lot of our favourite lollies have gone out of existence. We had for a halfpenny each nulla nullas, silver sticks, milk poles and lots of lollies which were 5 or 10 a penny. Conversation lollies, aniseed balls, milk kisses, chocolate kisses and lemonade was a penny a glass. The big thing was a spider — soft drink, usually lemonade with ice cream in it. This was dearer. You could get penny ice-cream cones.

Once we were all asked how many times a week we went to the pictures — silents, of course. One went 7 times a week (6 nights and the matinee). Another went 6 times and several went 4 times a week. Considering they were poor it seems a lot but there was a system of passouts, if you left the theatre at interval you were given a passout. Many theatres were continuous all day so it meant you got a passout when you were leaving. People, adults and children waited outside and someone would hand them a passout so they could get into the show free. It only cost 3d. for a child to get in if he had to pay. A theatre over Princes Bridge had concession tickets. These were lying around all over the footpath and if you picked one up you could get in for half price. Other dodges were worked, one kid would open the escape door into a lane and his friends would sneak in there. Parents must have given some of them money to get rid of them. The intelligence in class was pretty lacking owing to poor food and lack of sleep. Some would be apt to drop off in class.

As for us, Chris took us on Friday nights regularly, because we didn't have to go to school on Saturday. Usually we went to the Majestic in Flinders Street or sometimes the Paramount in Bourke Street. Perc did not come as it was still late closing on a Friday night. If it wasn't he would have been at a meeting. Perc was loath to miss a night at the Trades Hall but made an exception of Charlie Chaplin. He never missed Charlie.

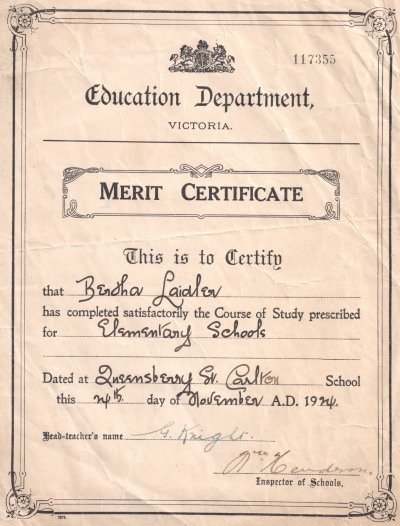

Bertha Laidler's merit certificate

In the sixth grade I got what was called a qualifying certificate. We had a nice teacher there but she made some reference to Yarra Bankers. I don't think she was referring to me but possibly Mark Feinberg's nephew who was at the Socialist Sunday School when I was there. How she knew any of us went to the Yarra Bank, I do not know. From there to the 8th grade, skipping the 7th. All classes from and including 4, were overcrowded even then. I failed to get my merit certificate on mathematics. I had a second year in the 8th and got my merit certificate and was dux of the school at 12½ years. That is to say I was female dux. They had a male dux and female dux. I got a gold medal for this.

At home I caused some consternation by flatly refusing to go back. Parents didn't bother to discuss their children's future with them as they do today. Especially, with his preoccupation with politics Perc would not be thinking about it. At some time there had been vague speculation about being a schoolteacher. To come out of jail and voluntarily go back to it and handle a mob like ours was the last thing in my mind. When I made the announcement Perc was very concerned. But after all, I had been encouraged to be a rebel so what could he do?

He had to get a special permit for me to leave and I did a year at business college learning typing and shorthand. I had two reasons for my decision. One was that having been through 2 years in the 8th grade already, I couldn't face a third. I had seen so-called scholarship students who spent most of the time on the ordinary 8th grade work as the teacher had little time to give personal attention to scholarship subjects.

Secondly I wanted to be independent as soon as possible and earn my own living. Chris's feminism got tiring and she was continually saying. "If it wasn't for you kids" which got the natural rejoinder "I didn't ask to be born". This urged me on to get out as soon as possible. The irony was that when I was ready to work I was still only 13½ years and Perc broke the news to me that though legally I would be entitled to work in six months' time at 14 years, it would be most embarrassing to him if I did, because he had been a strong advocate for the extension of school leaving age to 15 years and work to commence at that age. So, he didn't want me to start work for 18 months.

When I left school I never saw my great friend Dorothy again. I just felt it was the parting of the way — mine was atheistic and socialistic, hers was religious and conservative. It must have seemed terrible to them but I felt there was no future in it, and made a clean break.

Things happened at home during the school period. At school, with the war still going we were handed patriotic cards to collect money and I think stamps were put on the cards. Chris accepted a card for me and put some money out for me to take, rather than have me singled out. Unfortunately she mentioned it at home to her father. He went stone mad and raved at her for making me a party to the war. A war supporter, he couldn't get over it. He put on a sufficient display of anger for me to remember it 58 years later. It was not because he was German, but because he regarded it as a capitalist war. The whole family regarded it as a filthy trade war.

Then I remember the armistice and the mad joy of huge crowds in Bourke Street. Our place in Bourke Street was always a great vantage point for processions and we had a number of people there, including the Tunnecliffes. Perc, always wanting to be in the thick of things, or a showman if you like, held out the window a mask of a skull and the crowd went wild throwing fire crackers up at it. Finally the outside display box with Andrade's name on it caught fire and Perc had to run back and forth with buckets of water to put it out.

Hair was a big problem, I had plaits and every time Chris or Grandma plaited my hair it was a screaming match. They seemed to deliberately hurt. When "bobbing" the hair came in I was one of the first to have it bobbed. It was the time you had to endure all those useless strokes of the brush on your head as well. I don't remember when it was first cut, it may have been before schooldays or just after. Anyhow it was a blessing it was short later because in a poor school you are troubled from time to time with nits and lice. Chris had to comb out my hair with a fine tooth-comb every night to try and get the nits and lice out. They were hard to get rid of and I had them more than once. They are very contagious and no amount of hair washing prevents you contracting the curse.

It was fairly easily accepted that children should be bobbed but there was probably the most revolutionary fight by women in my lifetime over the question of women cutting their hair. Nearly all men opposed it and it was the topic raging between the sexes everywhere. There had been the fight of the advanced women for the vote and fights of narrow sections on clothing. At the end of the 19th century there was almost a worldwide campaign for women to wear what was known as rationals for cycling, a popular means of locomotion both for use and pleasure. Rationals putting it bluntly were long trousers, the first time women "aped" men. All this was nothing to the great women v. men contest on hair cutting, because it brought in the whole of the sex from the highest to the lowest. It was probably the only mass movement of women, in Australia. The men opposed it, no doubt, because it was really "aping" them. They wanted women to be clearly distinguished from them by their long hair. Long haired women bore the badge of servility and inferiority. As a child I heard it from Chris's women visitors, you heard it on trams and in trains. Women would say "My husband says if I get mine cut he will throw me out!" Well, women won because by far the great majority eventually got it cut and it had to be accepted in the end. I would suppose many a woman got a severe bashing or several bashings for standing up for her rights. It was a great release from the long wasted hours of doing it up in buns, some at the nape of the neck, some on top, some as plaited coils on the ears, some with bangs.

It seems a bit of a reversion today to go back to long hair for men and women. At least the girls should do what my grandma did (and probably lots of others), keep a bag and every time you comb out long strands you put it in. Then when you are getting sparse on top you have the hair, your own, made into a plait and you use it as a bun to bolster your own hair and conceal your baldness. If perchance you haven't gone grey it looks quite natural, or you can tint your grey hair to the colour it used to be. I would think working class men were not so one eyed, as Miss Vida Goldstein, a leader of the fight for women's suffrage wrote regarding a giant petition taken up and securing 30,000 signatures, "Never once were the canvassers met by a working man who said, 'I won't allow my wife to sign the petition.'"

I had my tonsils removed, this could have been before I started school or shortly after. The way it was done then, or at least the way I had it done was, we walked around to Collins Street to a specialist's surgery, Barry Thompson, I think, I was given an anaesthetic and tonsils and post-nasal growth removed in the surgery. When I came to, I was dressed and Perc carried me home down Collins Street, Russell Street and around the corner into Bourke street and home. No fancy hospitals then, or not for me. I rather fancy children at school did go into the Children's Hospital for the operation.

We never seemed to go to doctors nor they come to us. I had chronic earache, slight mumps, chicken pox and measles. The measles were bad. Chris used to talk a lot about Dr. Coue. I don't think she had much time for doctors. I was really ill with the measles with a raging temperature. The last thing I wanted was to have the lights on and Perc insisted on having it on. It was his peculiar way of getting me better. Of course it is one of the first things a doctor tells you, to keep the patient in the dark. I kept pulling the blankets over my head to shield my eyes. I got over it, without a doctor.

As a baby, Chris said I rarely slept. I have always had bouts of insomnia during my life. Perc used to tell us a story to try to put us to sleep. He told good stories, mostly about someone who can throw his voice and all sorts of pranks ensued from this. The trouble was, he would say a couple of sentences and then pause. I would say "Go on!" He would say, "What was I up to?" This went on right through the story. In exasperation I complained to Chris who frankly said, "He is preparing his speech for tonight while he is telling you the story." This was about it! Chris made her contribution, I will always remember her reciting Shakespeare's "Soliloquy on sleep". She thought that ought to put me off.

Eddie Callard.

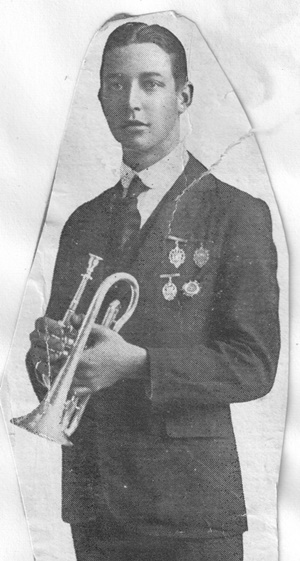

Early days the shop assistants were all nice revolutionaries who I could spend time talking to and who bothered to talk to me. Eddie Callard was my hero. He was, and still is, a very kind and sensitive man. He was Secretary of the IWW in Melbourne and greatly respected by the men and admired by the women. He now lives in New Zealand. Theo Farrall was the youngest of a family of revolutionaries. He was a champion cornetist. He was a fine boy and bothered to spend time talking to me as a child. Bert Henley came later in my schooldays and he also conversed. Vera Loyer was a niece of a former manager, and without politics. Later non-political assistants came in, Jack Mitchell and Bill Goss. Doris Warneckie was a typist who married Bert Henley.

Theo Farrall

There was another raid on the shop just after I started school. It must have been in connection with the IWW release committee work. Perc and Eddie were active in a Committee working to raise money for the families of the married men amongst the 12 IWW men framed and gaoled in Sydney. The Committee worked for a Royal Commission to investigate the frame up and ultimately succeeded. This committee started as a Defence Committee, outlawed it changed its name to "Workers Defence and Release Committee". This also was declared an unlawful organisation. Anyhow I remember the raid as it was on when I came home from school. It was a sloppy raid because the detectives were all upstairs on the first floor where a lot of books were stored. The shop assistants down below had taken their coats off and hung them out in the lane so that their pockets could not be searched. They took me outside to see their coats while the d's were upstairs.

In the early part of 1919 Australia was stricken with pneumonic influenza. It was blamed on the war and it was thought that the returning soldiers had brought it into the country. Many people died. Chris and Perc both caught it and were looked after by relatives. I went to Richmond to stay with my grandparents. Before leaving Bourke street, I recall seeing the funeral of Frank Hyett who died on April 24, 1919 from the disease. He was a thinker, speaker, debater, writer and organiser. He had been Secretary of the Victorian socialist party and was then Secretary of the Victorian Railways Union, later ARU. He was responsible for Unity Hall being built. His interests were wide and he was a member of Carlton Football Club and Cricket Team. He played interstate cricket for Victoria. The whole labour movement was shocked and grief stricken at losing such a splendid man. He worked so hard he probably had little resistance. He had the greatest funeral of any labour leader in Melbourne. The coffin was conveyed on a funeral train, filled with mourners and there were 100 cars and cabs on the road to Box Hill cemetery as well. A game of football was in progress at Hawthorn ground and at the sound of the train whistle the game stopped, players stood to attention, spectators removed their hats. Bob Ross and Harry Smith of the Victorian Socialist Party were allowed out of gaol to attend the funeral.

School gave me some exchange with other children during the play times and lunch-hour but I sorely felt the fact that I was cooped up when I came home. I couldn't run out and play like the others at my school. My life was one of observation of people, and as soon as I could read, reading. My early reading was all the comics (we had the lot in the shop and kept them clean and put them back), then the Ethel Turner and Mary Grant Bruce books — all in the shop.

Moses Baritz, centre

I clearly remember the visit, later in 1919 of Moses Baritz. He was such a colourful figure he couldn't be forgotten. I remember Guido Baracchi from an earlier date. While Moses was here they were both in and out the shop. Moses would be in two or three times a day. He had been deported from England to Canada during the war, after leaving Australia he was ordered out of New Zealand in 1920, and later deported from South Africa. He was simply a propagandist for socialism, and argued against the industrial unionists (IWW, One Big Unionists and general strike). He was famed as a debater and it was in July 1919 that he had a debate with Perc in the Strand Theatre. I had just turned 7 years. Perc had paced up and down the yard for a week beforehand preparing for his formidable opponent. The Tunnecliffes came to our place to tea on the Sunday night of the debate, which was held in a theatre named the Strand opposite. Tunnecliffe was very unhelpful by calling out interjections to try to embarrass Perc. Baracchi was in the chair. It was generally agreed that Perc trounced Moses. At the conclusion of the debate Baritz moved a vote of thanks to the chairman he said he thought Baracchi a very good chairman, but his criticism was "he sided with my opponent". Baritz had a complete contempt for women in the movement, regarding them simply as sex instruments. Almost certainly he had a contempt for children and never took any notice of me, but he was a personality I couldn't forget. Like many a stirrer he ended up respectable, a music critic on the Manchester Guardian.

Somewhere around this date we had a visit from two mysterious Russians who worked a duplicator all night. I was not to mention that at school.

Guido Baracchi, second from left, with Chris O’Sullivan and the Laidler family: Perc, Billy, Chris and Bertha.

Guido was a wealthy man who did not have to work for his living. He owned property from Little Collins Street to Bourke street, where the City Hunt Club Hotel used to exist. He used often to come up to Perc and borrow 3d. for his tramfare home. Why? No one knew. Possibly he wanted to feel on par with the others. In those days well off men or university people around the movement were very rare and usually had some sort of inferiority complex confronted by the proletarians, some of whom were contemptuous of "intruders".

One, who I came to know by sight was Maurice Blackburn. He would walk down from Parliament House at the top of Bourke Street and look in on the book shop, not so much for conversation as to browse through anything that was new. He was a familiar figure and was greatly respected by Perc with the reservation, put into words with some disgust that he was religious.

Mock recruitment poster by Tom Barker of the IWW. (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

Donald Grant had been given 15 years in jail for 15 words — the 15 words being "FOR EVERY DAY BARKER IS IN JAIL IT WILL COST THE CAPITALISTS TEN THOUSAND POUNDS." He became a senator and always visited Perc at Melbourne Cup time. Tom Barker, of the IWW had been given six months for his famous poster which read: "To arms! Capitalists, parsons, politicians, landlords, newspaper editors and other stay-at-home patriots, your country needs you in the trenches! Workers, follow your masters." This was produced for the anti-conscription campaign. Tom became a mayor of St Pancras and hit the headlines when he flew the red flag on the town hall on May Day.

A lot of union delegates at conferences stayed at Parer's Crystal Palace Hotel an ornate building of the past and as it was opposite the shop anyone but a rabid right-winger called in. This way I saw many of the celebrities.

I first learned of Chris's capacity for duplicity when Premier of South Australia, Jack Gunn called in. He had great pleasure in his high office and I remember her praising him and telling him how hard he was working etc. I was very impressed. He left and she said, "The silly conceited arse!" Apparently things said were not always meant, I had learnt. Perc would have reacted differently, he would have said something to his face in a pleasant manner but which would have gotten the message home.

As another instance of Chris's guile — my second name is May. It was typical of Chris when she told me, "I decided to call you May because Perc has a sister called May, my brother Albert married a May, brother Ernie married a May, a great friend is May Rancie (sister of Norman of the IWW) and another friend is May Jones." No doubt she knew other Mays. Chris said they will all think you are named after them, so at least 5 Mays were pleased in her estimation. I don't know whether she went so far as to tell each of them that I was named after them or whether she left it to them to imply it.

In 1921 Eddie was sent to Sydney to manage a shop opened by Andrade. He came back to Melbourne on holidays. I recall Chris organising a party in his honour on one occasion.

In 1921 there was the exciting illegal visit of Paul Freeman. He was a long thin man who wore dark glasses. It was obvious from Perc's excitement that he was of some importance. Freeman had been deported after big demonstrations in Sydney had shown support for him to stay here. He had managed to get to Soviet Russia. Now he came back with a false passport to convey news of Russia and to recruit delegates to attend the Red International of Labour Unions Congress. As there was no Communist Party at this time in Melbourne, it having collapsed, Perc, was asked by Freeman to organise a Melbourne meeting for him to address. Chris must have insisted that Perc take me with him on his tour around, contacting people. I still remember the seriousness of his lecture to me. It was to this effect: "You must not say anything about this man at school. The police want him and if you tell any girl and she tells her parents, it may be that he will go to jail and it will be all your fault. You wouldn't like that would you?" I didn't tell anyone. I learned to keep my mouth shut when necessary. The meeting went off successfully and Mick Considine, then in Parliament took Freeman to the Parliamentary dining room for lunch. I suppose they felt they had a laugh on the establishment by doing this.

Mick Considine

Mick Considine was a frequent visitor to the shop and used to talk a lot to Chris. He was another man greatly respected by Perc. Perc could not resist any demonstration or procession and we went around to Collins Street to see the Eucharist procession. Perc was shocked to see Mick marching, as he thought he had lost any Catholicism he had in the past.

I remember, possibly again before I started school, a visit from the syndicalist poet Lesbia Keogh. She was a great friend of Guido Baracchi. She married a well known New Zealander, Pat Harford. Lesbia was ill and had not long to live. When she visited, Perc picked her up and carried her up the stairs to save her exertion. Perc was short but had trained as a physical culturist and was very strong. Lesbia was a fragile but strong-minded woman. Someone in Sydney was compiling a book of her poems and stories about her in it but I don't know what happened to this venture. Lesbia's brother only died recently, he was a doctor and was in charge of the Cancer (Anti-Cancer) campaign in Melbourne. He had been a radical in his youth, too.

The Trades Hall became a place well known to me. Perc was there because he was on various committees and active in the Labor College but even if he had no meeting he went there, just to talk to anyone else going to a meeting. Often he was supposed to be just going out to see somebody on some particular thing and I would go with him. The conversations always dragged on interminably and I got used to just standing around till he finished.

If he had a meeting its conclusion didn't finish the night. He would talk around with anyone still in the Trades Hall and then walk down Russell Street with anyone going that way. They would stop on the north-west corner of Russell and Bourke Street and then the discussion and debate would really begin. The trams would stop around mid-night, the cabs and cars disappear, and loud and clear his voice would waft up to us in the bedroom on the second floor. With his voice trained for public speaking, it would carry as though at the bottom of a canyon. Chris would say, "Oh for Christ's sake why don't you shut up and come home." He didn't hear it, but I did.

Came the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1921. His parade was another one for which we had a full house of onlookers at the two windows, first and second floor. We had a good view of the Prince who was cheered, but in front of him were the escort mounted troopers who were hooted, and behind him was Prime Minister Hughes who was hooted. The Prince must have heard the hooting and probably thought some of it was for him. Tunnecliffe gave us invitations to go down the Bay to meet the ship the Prince was on and to a reception at the Exhibition Buildings. We were sitting with a number of Labor Party people and I was surprised to see some of them whizzing off bottles of lemonade and putting them in their pockets. Perc didn't bother with these invitations. At school we were trained to take part in a display at the MCG. We spent a long fatiguing day, or so it was for younger children. We formed some giant word and although I had a photo of it for many years I can't remember what it was. Something patriotic no doubt. We were trained as a choir to sing at the Exhibition Buildings and children from all schools took part.

We went out to Tunnecliffes when Browning Mummery, the singer visited. He had been plain Joe Mummery in the Victorian Socialist Party and had sung duets with Bertha. He had become a world-class singer, as Browning Mummery. He only died in Canberra early in 1974 where he made his final home.

A frequent visitor around this time was Eric Ashe, nephew of a famous actor, Oscar Ashe. When Oscar was here playing in Chu Chin Chow Eric took Perc to meet him. Eric had been in Russia soon after the revolution and was a keen supporter on his return to Australia. Eric had shaken hands with Trotsky. He had an automobile and it was the only time we drove out in style. We never had a car at any time but Eric would take pleasure in driving us around. One Sunday he drove us all to Monbulk. Perc didn't want to go because he had some reason that he wanted to be sure of getting to a meeting at the Bijou Theatre that night. He was finally persuaded by us all. Eric said nothing could go wrong. We got bogged in deep mud in Monbulk with no hope of getting out in a hurry. Perc was furious at missing the meeting. Either he had something special to bring up or his non-appearance would be interpreted by some as squibbing some issue. The meeting was over by the time we got towed out and back to the city.

Eric was a nice well meaning chap and as most others did he confided in Chris. He didn't know whether to marry Beryl Woinarski of the legal family. Chris told him, "If you marry her, we'll never see you again." He strongly denied this suggestion, but it was true. He married her and we never saw him again. She was quite successful in taking him out of the movement. Ironically when the unemployed in Darwin flew the red flag in the Administration offices in Darwin, he was working for Crown Law. The unemployed locked a few of them in a room, including Eric.

I went behind stage with Perc when we went to see Frank Neil. Frank came from Corindhap and made quite a success on the stage. He produced and acted in a number of suggestive plays such as "Up in Mabel's Room", "Getting Gertie's Garter" and similar at the Palace Theatre near Spring Street in Bourke Street. He also produced and took the lead in "Charlie's Aunt" and did it very creditably. I was amazed to see the actresses sitting in the wings, one knitting and chatting and right on the dot she would drop her knitting, throw off a cardigan and be on stage saying her lines. It seemed to be an automatic reflex action because no-one gave her a cue.

A lot of world class magicians, jugglers, ventriloquists, etc who were performing at the Tivoli used to come into the shop. There was always a variety of interesting callers whether political or theatrical.

Sunday nights we would go to lectures, having progressed from early years at the Victorian Socialist Party, to the IWW, then the CP. We then used to occasionally go to the Rationalist lectures. These were held in the Empire Theatre a small theatre known as the flea-house in Bourke Street between Russell and Exhibition Street. Here the lecturers were usually J.S.Langley or Harry Scott Bennett. Always in the front row was Dr Omero Schiassi the Italian who had fled Mussolini because he was known as an advocate for the Seamen's Union in Genoa.

We didn't have much for entertainment at home. At one time the whole family went out to Collingwood and bought an old fashioned gramophone. One of those that you put on round cylinders, called rolls I think, instead of disks. I suppose we got this old fashioned thing because it was cheap. We bought it from a man named White whom Perc knew. He had a second hand book and junk shop. Sometimes I went out to buy new rolls and he was always pretty drunk. Sometimes he would be lying in a stupor at the back of the shop. It was only a few years ago that I learnt he was a famous anarchist along with Chummy Fleming in his youth. Probably Perc told me at the time but it did not register. We used to play the phonograph every night for a while. My grandfather had given me an old autoharp and a book of tunes to play. I was never able to learn it.

We usually went away for holidays. Chris thought we needed it living in the city. We would go to Belgrave, Olinda, and we had a good long holiday at Chelsea one Christmas because an outbreak of measles led to an extension of our holidays. Chris and Perc didn't tell us lies and it was here that I consciously remember the first lie being told me by an aunt. We had different friends come and stay with us and an aunt and cousins. A fishing expedition was being organised by an old German friend and we children were allowed to think we were going too. We knew we had to get up at some unearthly hour, get in a row boat and row out to sea. I was looking forward to the expedition with great anticipation. When I woke up next morning at the usual hour and found our fisherman had gone long ago I was indignant. My aunt simply said "Children don't go fishing." I had been led to believe something she had known was not going to happen at all, the previous day. I never forgot it. Adults shouldn't lie to children. Another lie I never forgot emanated from the family of my girlfriend at school. They were devout Methodists and they knew I was an atheist. I had been there to a meal and they asked me to say grace. I said "Grace". I'd never heard of it. They persuaded me to go to the annual Sunday school (or Church) picnic. I went on condition there would be no religion at it. Given this assurance I went along. Of course they started at the church with prayers. I should have gone straight home because I sulked all day at this betrayal. If they regarded it as a lie they knew god would forgive them because they thought I was a sitting shot for conversion. It made me more irreligious than ever.

Once when my Corindhap Aunt May was down in Melbourne for medical treatment she took me back with her to Corindhap. She was very strict and proud. We went the way we usually did to Corindhap, train to Geelong then change onto the Ballarat train getting off at Bannockburn and from here by motor coach. The horses had been replaced but the journey was nearly as slow because the car kept breaking down. The tires kept getting punctured. Probably the road was rough and the driver didn't know too much about cars and possibly the cars had not been perfected to any extent. Anyhow we always had trouble. On the train May met people she knew who were travelling to Corindhap. They were jolly people and were eating most of the time, cold sausages and grapes. Naturally they offered some to me but May insisted I didn't want them. It ruined my trip. She was too proud to let them think we could be hungry enough to eat their food. When we got there, the vegetables were parsnips and carrots, which were revolting to me. Chris would put them in soup or stew diced up but never serve as a separate vegetable. There is a tendency in her family to regard root vegetables as very inferior to green vegetables. My grandmother always referred to white turnips as pig's food. At Corindhap someone, probably May who would have seen how we slathered the butter on, in Bourke Street, told me to spread as much butter on my bread as I did at home. They told me not to be frightened but to go ahead and do it. Frankly fresh home-made butter was repugnant to me as they had no form of cooling and all butter was made with sour cream. We did overdo it at home. Jam and cream on a slice of bread was a treat for most kids but we had bread, thick butter, jam and cream.

Early days my Corindhap great grandmother, granny Greenwell was still alive. She lived in a little room on its own and every day would call Ron, my eldest cousin and myself and give us the money to go down the store to buy some biscuits. We ate them all the way back and then she would reward us for the errand by giving us some, no doubt knowing we had been stuffing ourselves before hand. She was a kind-hearted woman.

William ("Son") Laidler, second row from back, arm in sling.

I was still pretty young when we went to Corindhap for Son's funeral. He had a bad arm injury gained at the war, which gave him much pain. My grandmother with the death of two sons never went to any social functions any more. She never said if she regarded it as permanent mourning but probably it was. In the country they are proud of the number of cars at a funeral and the twins (the youngest in the family) and I, were up on the wood heap and they counted the cars as they went by.

Occasionally I went for a week end to a rich friend's house in Dickens Street St. Kilda. There was a billiard room, tennis court, pavilion and garden chairs and a rose garden. All reminders of earlier days. I only once rode in a hansom cab and it was from this place to the Hospital in the city and we rode all the way down St. Kilda Road to town. It was a great trip.